Blog #16

A nervous system that is dysregulated will cause enough trouble on its own. However, when you bring two dysregulated nervous systems together, you get more than double trouble. This is commonly known as a relationship; between family, friends, colleagues, acquaintances or lovers.

We’ve all had trouble with all of them, but in this blog we are first going to look at romantic relationships because this is where we see the extremes of our nervous systems playing out in relationships.

Two Different Dysregulation Problems

The key to understanding romantic relationships is that our nervous system affects them in two completely separate ways. These are often confused.

Firstly, we are set up by our childhoods to have what is known as ‘attachment styles’. Broadly speaking, these are our ways of imitating the over- or under-reacting nervous systems of our caregivers. We learned from them and so we copied when trying to grow into becoming adults.

Secondly, we also have our own dysregulation left over from all of our unfinished responses to threats in our lives. This also leads to over and under-reactions to triggers. (But not always; we might get lucky and have a response to a stimulus which is just right, the Goldilocks response.)

These two different influences on our behaviour can get confused, because they both seem to involve doing something too much or too little; being too close or too far, or being too overwhelming or too shut-down. It can be hard to separate them and therefore to know what to do about them.

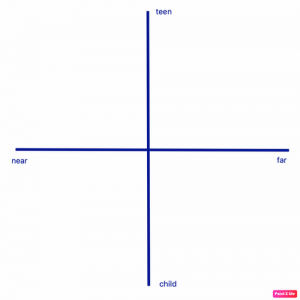

So, here’s a new way to look at it which might make it clearer. Instead of talking about attachment and trauma (the traditional labels for the above, which can then get confused), we are going to model this as Proximity and Behaviour. We can then see that taking steps to alter one can, over time, alter the other.

Proximity

Our attachment set point from childhood can be reframed as our desire for proximity. This can make us want to have others closer or further away. But it is not always obvious how.

For example, if you have a very overwhelming, out of control parent, then you are likely to copy that and become out of control yourself. You might not think you are, but you are likely to become more extreme in a romantic relationship. You do too much, say too much, try too hard, control too much, and eventually you find that these relationships make you out of control. So, your strategy for feeling ok is to keep relationships slightly at a distance. Then you feel better, more independent, and safer.

However, if you had a very distant, absent parent, then you are likely to copy that and to be distant or shut down in your own relationships. This will make you feel anxious and alone and therefore want someone to be present all the time for you. You will want the other to be close, so that you can feel alive again. Losing that will feel very worrying.

You can model this set point on a continuum. Attachment theorists often label the ends something like anxious and avoidant, with secure in the middle. Addiction counsellors often call them love addict and love avoidant.

I’m just going to call the end points of this spectrum of proximity ‘near’ and ‘far’. The middle is ‘just right’.

Behaviour

The dysregulation in a person’s system will be worse from the same life events if they are already struggling from early childhood to manage connection safely. This leads to more unfinished business in their nervous system and thus they become prone to over- or under-react to life’s triggers as adults.

Behaviour therefore is also on a continuum. We could say one end we over-react, on the other we under-react, and in the middle it is just right. But I’m going to label the extremes ‘child’ and ‘teen’. The middle is ‘adult’.

This is not the same thing as your attachment style or desire for proximity. For example, people can have great early childhoods and then become dysregulated by extreme events later in life. Equally (and here is the great hope here) you can have rubbish early childhoods and yet work hard to behave as if you have no baggage at all.

There’s nothing you can do about your early childhood, but you can decide to aim to have different behaviour. You can try to simulate the behaviour of someone who does not have any baggage, is not triggered, and is therefore reacting just right.

And the magic is that if you do, then you can also change your attachment style, or appetite for proximity. Here’s why.

The Relationship Matrix

If you draw a simple grid with these two qualities on two axes at right angles, you get a diagram which looks like this.

A lot of the time when we talk about relationships, we think that these two qualities of behaviour and proximity are the same. They are not. But they are often seen together. (It is important to note that they don’t necessarily cause each other, just because they often are observed to come together, technically the difference between correlation and causation).

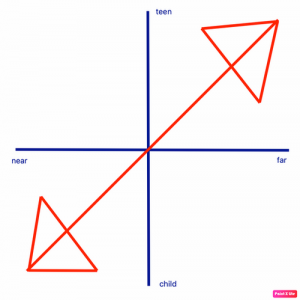

Generally speaking, we find that people who prefer someone else to be ‘far’ are more ‘teen’, and people who prefer someone else to be ‘near’ are more ‘child’. These are the two different effects of having grown up around the people who looked after them. So their difficulties in having relationships is then blamed on their behaviour. But it doesn’t always feel like that. They can feel the same pull to be near or far, regardless of how they are behaving. And then they find that destructive or shut-down behaviour makes these already troubled relationships worse.

So people in relationships usually find themselves heading towards the top right or bottom left of this map, and if they go too far then the relationships can get into real trouble.

What can you do? You can’t change your attachment style easily. It is part of the way your brain is wired from childhood. But what you can do is to change your behaviour.

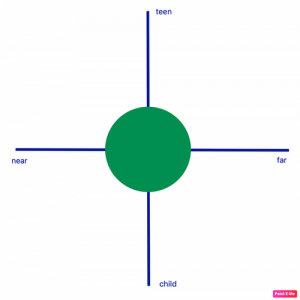

So the key to relationships is to learn the behaviour of people who live in the middle of this matrix. This has two wonderful benefits.

Firstly, you get to have a better relationship, because your behaviour is more safe for each other.

Secondly, if you practice this well over time, you will start to move your set point of proximity for relationships in the first place. You basically drag your attachment system into the middle of this matrix, often kicking and screaming, by using your brain as if you were already in the middle of it.

Fortunately, our brains remain plastic and so if you can offer and receive a new quality of relationship, over six to twelve months you will start to physically rewire your brain and its attachment system. So, you want to get off these red arrows and into the green zone.

And it is easy to do. The key is to offer the other person psychological safety, which we do with containment, and ask for our own, which we do with boundaries. And then they do the same. But it matters how you do it.

In the previous blogs we have looked at how dysregulation was born and what it has done to our behaviour, learning about boundaries and containment. In the next blogs we are going to look at how this creates different relationships, and how we can use these ideas to heal them.

This changes us fast and it changes us slow. We can have dramatically different and better relationships as a result of changing our behaviour, and also change the whole map of the kind of relationships we are looking for in the first place.

You can download this post in a handy 2-page PDF to print and share with friends, family, clients or colleagues. Follow this link to download now.

You can buy a copy of The Invisible Lion now on kindle or paperback from your local Amazon store. Just click here to buy now.