As we develop from children to teenagers to adults, we carry each stage with us into the next. We all have a child, teenager, and adult within us, influencing our behaviour.

The child is the part of us that seeks comfort and looks to a caregiver or saviour to rescue us from difficulties, and is characterised by taking no action. The teen, or adolescent, is a bit more difficult and boisterous, sporting a ‘whatever’ attitude to life. The lack of a sense of adult responsibility can be quite enjoyable for a time, but the consequences soon catch up. The adult, then, is the part of us that is responsible and cooperative, taking action with everyone’s mutual gain in mind.

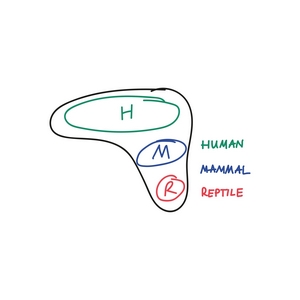

There is another set, or model, of three parts of the brain that affect how we live our lives. This is the divided brain, and it looks something like this:

Over the course of millions of years, layers upon layers of adaptations were developed in all species, resulting in the diversity of life we see on Earth today. Even our own brains have been built up in these layers. We are the result of reptiles becoming mammals and mammals becoming human. We even have within our brain three distinct brains. One functions like our reptilian ancestors, one like the mammals and one like a human. So, we can say that we have a reptile brain, a mammal brain, and a human brain.

The Executive, Or The Adult

The executive branch of the brain seems to have some control over how we apportion our energy to these different parts of the brain.

This place is called our prefrontal cortex, or to put it another way, our adult. This is who we want to have in charge. The adult manages our boundaries, helps us to practice containment, and then, once properly educated about the nervous system and its regulation it will help us to allow our mammal brain the appropriate time and space to heal our nervous system.

Now you’re aware of these parts, it can be a useful exercise to start to measure how much of us is in our child, adolescent or adult reaction at any one time. Take that meeting, for example, where you wanted to walk out during the boring presentation. Are you 50% adult in that moment? If so, is the rest all that teenager? Or underneath that, is there a frozen child, trapped in this room and wishing she could run away? How much of each of them are you struggling to maintain, with your calm, smiling, listening, not running-away adult, I wonder?

It can help just to acknowledge the conflict and name these parts. Every day when I start writing, if I’m lucky, I’m probably 20% a child who wants to give up, 30% a teenager who just wants to watch YouTube, and maybe 50% an adult, which is why I actually start to write. It’s a battle.

This battle can be baffling. Ever wondered why you waste time procrastinating, or end up doing things you didn’t want to do, or have failed to reach your calmly and logically calculated goals? This is why. Not only is our nervous system dysregulated, but each of its dysregulated reactions can take hold of us in different parts of our brains. These parts of the brain can co-exist and fight it out with each other for who is going to get the most control over what we do next.

Believe it or not, our brain’s main job is to run our bodies. So, whichever part of our brain has majority control is going to determine what our body is going to do. Doing is how we show our behaviour. And our behaviour affects our relationships, which affects everything we think we need to feel safe, such as a family, a partner, and a job.

That’s why, if we don’t get on top of this warring brain of ours, we can end up making our world less than safe for ourselves.

But we can start to dismantle this vicious cycle of safety and behaviour if we open up a window into the question of where to put our energy while these parts are trying to take control. If we can find our adult, we have a chance of making ourselves feel safer, because adults make things safe. And if we feel safer, we will probably have fewer triggers and fewer reactions. And if we can do that, we might get even more power into our adult. And so on. It’s like a government that is working properly, finding compromises in the greater interest of the nation as a whole.

Recovery is possible. We are not necessarily slaves to our brain and body biology. Through learning and some directed effort we can begin to swing the wild workings of our brain and bodies back to our favour. It starts with self-awareness.

Minority Parties

The brain is a fabulously complex organism. My book, The Invisible Lion, offers a straightforward model, because that is enough to help our thinking brains to understand ourselves better and take some positive steps to improve our lives as a result.

But other, more complex models are interesting to visit briefly too. Janina Fisher has a very elegant formulation, leaning somewhat on the work of Dick Schwartz and Pat Ogden. In these expanded ideas, you might find some aspects of yourself which you recognise and it can be a relief to know that all of these life experiences, some of which we even blame or judge ourselves for, are simply the inevitable consequences of being a human mammal with a dysregulated nervous system.

On a basic level there are three possible responses to a threat: over-reaction, under-reaction and the just-right Goldilocks reaction. But what if I told you there are also responses we have before we get to this point, and perhaps even after, too?

When we (and other mammals) first become aware of possible trouble, something in us changes. We think of animals pricking up their ears; imagine a rabbit in a field as it picks up the scent of a fox, for instance. The rabbit narrows its focus and its whole physiology is now orientated towards the possibility of threat. But this is not really a reaction, yet. It’s a defensive orientation, preparing you for the possibility of having to react to a threat. You become more vigilant.

The interruption of normal life from a peripheral awareness of a threat can be described as switching off the social engagement system. When we are calm and healthy, we are typically socially engaged with other people. Or to put it another way, we’re connecting to them in a collaborative and cooperative way. And that’s because we are trying to make allies and to be safe with them. If we get a sniff of not feeling safe, this engagement may stop because we then may need to become competitive and combative to survive, retreating back to our earlier mammal brains.

Some people feel threat in their lives all the time. They might find it hard ever to be in their social engagement system and to connect safely to other people at all. By comparison, other people find great comfort and safety in making these connections, and they reduce threat in their lives by having good relationships and networks.

Help Me

Just before we mobilise our fight or flight reactions, we have another option. If a threat is detected, we can look for help before we have our own independent reaction to the threat. Non-human mammals do it too. In fact, it works very well for young mammals to call upon a larger mammal, like a primary caregiver to come and change the dynamic of the threat. Once this larger mammal comes to the rescue, the threat goes away and the young mammal doesn’t need to work through a full-blown reaction. The situation is diffused.

We all have this memory from childhood; for some of us, this threat response worked out well. For others of us it was not so successful. So, each of us now has a different idea of who to cry for when we need help. From a child running for their mummy, or a special forces unit calling in air cover, it is a completely logical response to a threat to try to get the threat taken away by someone else bigger or stronger than you before any flight or fight is necessary. The instinct is very clear.

This also helps to explain why we are all so interested in identifying ourselves with larger groups. People follow sports teams, identify with people who love the same things, join gangs, or get very invested in their nationality. All of this helps us to feel safer. We belong to something. We are attached. This activity of forming groups within groups within groups is seen in most higher functioning mammals. If we have a family, or a group, or a gang, then we have something bigger and stronger than ourselves to cry to for help when life gets threatening. This keeps us out of fight or flight and further away from life-threatening danger. The people who have the most dysregulated nervous systems and experience the most real threat in daily life will cling most strongly to this dynamic, like the inner-city gangs of disadvantaged youths that can be seen in cities the world over.

Dead Faint

At the other end of the spectrum is a variation in our freeze response. We have described freezing as an under-reaction. There are actually two ways that the nervous system does this and we’ll be familiar with both from metaphors from animal life. We say people who are overwhelmed are frozen like a deer in the headlights. When this happens, the deer is still standing up. It is so overwhelmed by the stimulus to take action that it locks up and doesn’t move at all. We might relate to this as being so fearful or panicked that we can’t do anything. We are frozen.

But there is also another way to freeze. Sometimes we talk about people playing possum. Possums freeze in a different way. They go completely limp, so would be unable to stand up like the deer in the headlights. What’s going on? This is an example of the reptile brain having completely taken over from the mammal brain, sending the animal into a very low state of arousal. This is the freeze you can see in the discharge video on the resources page of The Invisible Lion.

We might most easily relate to this as a state of submission. Sometimes, we just give up, unable to fight the threat anymore. We give into the inevitable and no longer have any will to change the outcome. Humans don’t do this often, but we can feel this flat sense of complete submission, of giving up, in the mix of the various parts of ourselves, courtesy of the hung parliament of our complicated brains. There are all just waypoints along our familiar threat response cycle.

You can download this post in a handy 2-page PDF to print and share with friends, family, clients or colleagues. Follow this link to download now.

You can buy a copy of The Invisible Lion now on kindle or paperback from your local Amazon store. Just click here to buy now.